Get the Popular Science daily newsletter💡

Breakthroughs, discoveries, and DIY tips sent six days a week.

There are plenty of studies examining why humans are so hardwired to detest spiders. However, fewer researchers have spent time investigating just how far we’ll go to avoid even looking at them.At the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, psychologists decided to find out for themselves. Their findings, recently published in the journal Frontiers in Arachnid Science, indicate people will gaze at almost anything other than spiders if given the option—even if it’s another arachnid.

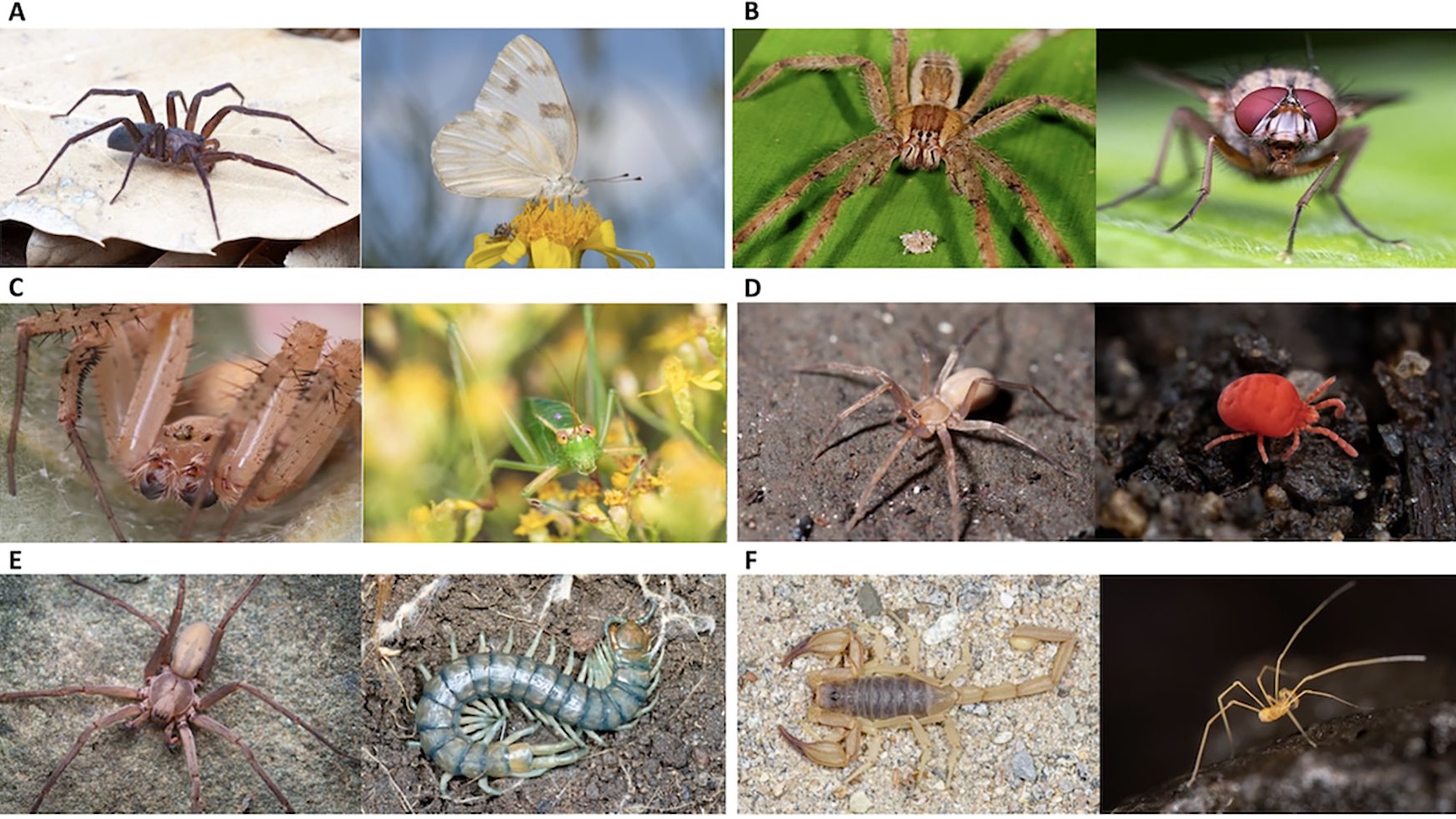

But before they could analyze anything, they needed volunteers. The psychologists recruited nearly 120 (brave) participants to stare at 13 sets of side-by-side images of various spiders, insects, scorpions, and other arthropods. For example, one duo featured a spider next to a butterfly, while another showcased a scorpion beside another arachnid. Eye-tracking cameras then recorded their focal points over a set span of time before moving on to the next image set. Finally, study volunteers completed a brief survey to gauge their overall attitude towards spiders, including any strong feelings of arachnophobia.

The study’s authors assessed four eyetracking metrics: how long someone spent on each image (dwell time), how long they initially fixated on a specific photo detail (first run dwell time); the length of time before they shifted eyes towards another subject (first fixation time); and how often a volunteer returned their gaze to an image during the trial (run count). The results? People really aren’t fans of spiders.

“Findings suggest a general avoidance of spider images in the presence of other non-spider arthropod images, as well as avoidance of scorpion images in the presence of non-scorpion arachnid images,” the study’s authors wrote, adding that, “Across all metrics, there was a tendency to record longer first fixation times, shorter dwell times, and lesser run counts toward images of spiders.”

At the same time, not all spiders (or parts of spiders) elicit the same disgust. Among the photo selections were sets that compared specific anatomical arachnid attributes like eggs, fangs, webs, and hair. Similar to prior research, people often prefer their spiders relatively hairless.

“If these additional characteristics might also be considered fearful or disgusting…individuals should be more likely [to] avoid images of spiders with these additional characteristics,” they theorized. “This pattern is precisely what we found for hairy spiders, which generally received less attention and a slower first fixation time relative to non-hairy spiders.”

Meanwhile, the authors were surprised by other data results. Participants often appeared to draw their eyes towards details that may suggest the presence of spiders, plural. This contradicted their early predictions. The scientists theorized that this may simply relate to the number of additional image factors that garner interest, or a propensity to assume objects like webs and eggs denote calmer spiders instead of speedier, jerkier, or otherwise unpredictable arachnids.

Although participants weren’t thrilled at the sight of most spiders, some species received at least some grace. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these were arachnids that humans generally anthropomorphize more than their relatives. Smaller jumping spiders with larger eyes frequently generate more aww’s than eww’s, probably because they possess two larger, more human-like eyes.

“When spider images are the only option to attend to, there seems to be a greater bias to the more human-like arachnid. Additionally, jumping spiders that were colorful were favored more over regular jumping spiders across all measures, likely due to a combination of both anthropomorphizing and the saliency of color in guiding attention,” the authors wrote.

Beyond giving volunteers the “ick,” the study’s results may have real benefits across multiple areas. Focusing on spider traits that “elicit engagement rather than avoidance” could help improve science communication efforts, conservation projects, and even exposure-based phobia intervention treatments.

2025 PopSci Best of What’s New

The 50 most important innovations of the year