Snow-dusted furrows etch the fields as trucks cart away mounds of dirt, day and night, to level the ground. Around the perimeter, blue signs mark the 672-acre site where, over the next two years, steel-framed buildings holding towers of computer servers will rise – part of a frenetic coast-to-coast drive to scale up AI processing power.

To Ted Neitzke, the mayor of Port Washington, this $15 billion data center project is a huge win for this harbor town on the western shore of Lake Michigan. It will generate new tax revenue and hundreds of permanent jobs – not counting the construction workers and contractors already pouring in. Mr. Neitzke, who balances his part-time job as mayor with his work as chief executive of an education nonprofit, grew up in the city of about 13,000 when it was still a manufacturing hub for lawnmowers and snowblowers, before the factories moved away. Now, it’s more of a bedroom community for Milwaukee, with a historic lighthouse and a summer tourist trade.

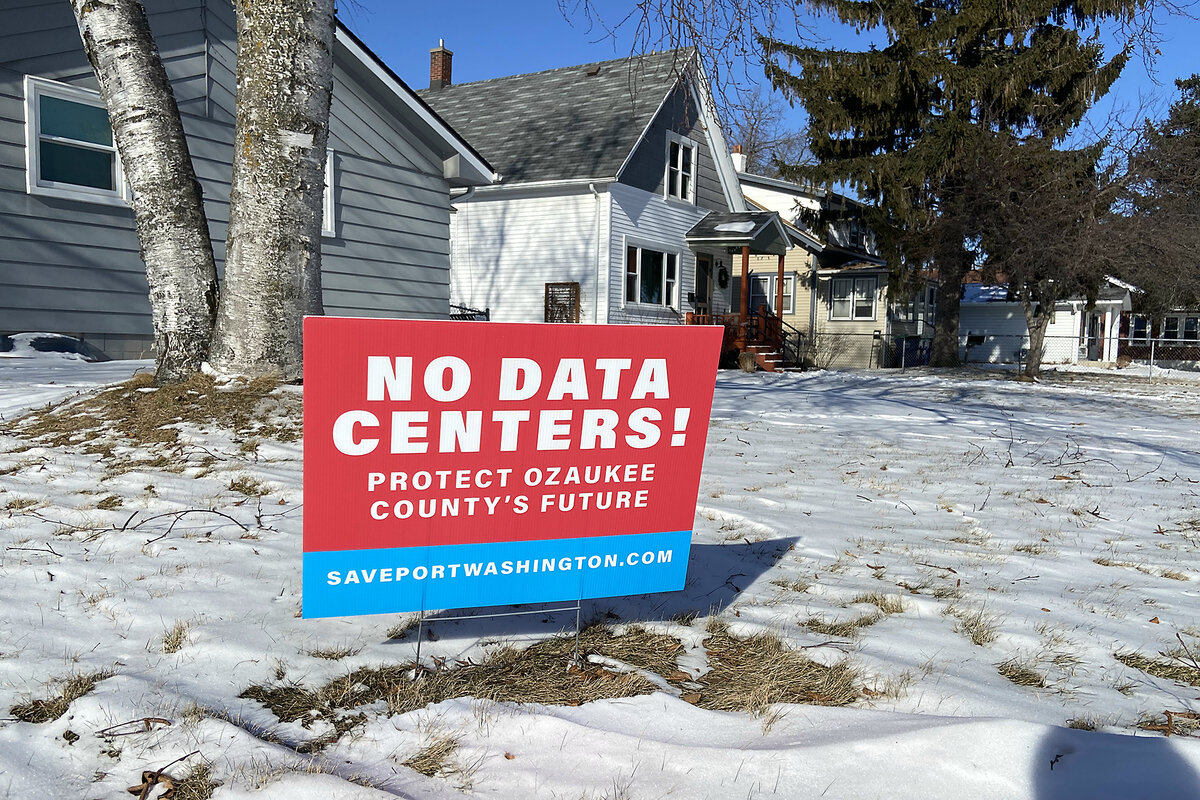

Lately, though, Port Washington has become something else: the epicenter of a backlash against the giant data centers that are mushrooming on available land all across Wisconsin. The controversy has engulfed Mr. Neitzke and his city.

Why We Wrote This

Concerns about electricity bills and local impacts are fueling bipartisan opposition to the massive data centers that power the digital economy, from cloud services to AI chatbots. In Wisconsin, as in other states, the tussles are personal – and fraught.

“I didn’t choose to be the face of data centers, AI, or energy [usage], but I was, because I’m the mayor,” he says.

Simon Montlake/The Christian Science Monitor

Mayor Ted Neitzke of Port Washington, Wisconsin, stands outside City Hall, Jan 25, 2026. Mr. Neitzke is the target of a recall campaign after his city approved a $15 billion data center to be built on former farmland. Tech companies are rushing to build data centers across the country to expand AI capacity and meeting pushback from local communities.

It’s a fight flaring across the country, in red and blue states, from Oklahoma to Indiana to Pennsylvania, pitting big tech companies and their partners against local activists up in arms about the environmental and community impacts of data centers, as well as potential disruptions from the artificial intelligence technology they make possible. Power-hungry data centers are also being blamed for rising electricity prices. That issue was central to November’s gubernatorial elections in New Jersey and Virginia, the latter of which has the largest concentration of data centers in the country.

It also helped Democrats in Georgia win two GOP-held seats on the state’s utility regulatory committee in last year’s special election. Legislators in Georgia are now considering several bills to regulate the data center industry, including its effects on electricity prices and the tax breaks it receives; one Democrat-sponsored bill would impose a one-year moratorium on new data center projects.

Democrats in the U.S. Senate are seeking to investigate data centers’ impact on household rates. “Recent increases to consumers’ utility bills are directly linked to the tech industry’s data center buildout,” wrote Sens. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, Chris Van Hollen of Maryland, and Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut in a December statement.

An October analysis by the Bank of America Institute found that rising demand for power for data centers and manufacturing facilities is already leading to higher utility bills for residential customers, and it predicts the trend will continue as more data centers come online. Low-income households are disproportionately affected by higher utility rates, the analysis noted.

Lawmakers in Wisconsin recently passed Republican-authored legislation to regulate data centers, introducing protections for consumers when new capacity is added to the power grid. The bill would require any renewable energy facility that serves a data center to be on the same site. However, Gov. Tony Evers, a Democrat, is expected to veto it; Democrats in the legislature have drafted their own bill, which includes strict labor and environmental provisions.

Brad Teitz, a director of state policy for the Data Center Coalition, an industry group, says the bill that passed “misses the mark” in the regulation of power usage by mandating that solar farms be built alongside data centers. But he says the industry wants to work with lawmakers to “spur collaborative and sustainable data center development. Wisconsin is right for that opportunity, if folks want to allow it.”

Shouting matches at city council meetings

In Wisconsin, as in other states, tussles over where the tech industry should build the data centers that undergird the digital economy, from cloud services to AI chatbots, are local and personal – and explosive. In Port Washington, council meetings have turned into shouting matches and led to arrests of activists who oppose construction of the data center.

Mayor Neitzke says he’s done everything possible to share information and to allay residents’ concerns about power bills, water usage, air pollution, and wildlife protection. “Everyone who came to our council meetings, who would say, ‘This isn’t right, this isn’t fair,’ we would write it down. We would investigate it. And if we could control it, if it was within our control, we would do something,” he says.

Simon Montlake/The Christian Science Monitor

A yard sign in Port Washington, Wisconsin, reflects local opposition to a $15 billion data center under construction in the city of 13,000, Jan 26, 2026. Wisconsin has several data centers proposed or under construction, part of a massive buildout of AI capacity across the country. City officials say the data center will provide jobs and tax revenue.

None of this has mollified critics of the project, which is being built by Denver-based Vantage Data Centers and will be operated by Oracle for OpenAI. They question whether its long-term power demands can be met without raising costs for other users. They argue also that the city hasn’t been transparent and object to a tax-financing package that defrays Vantage’s upfront costs.

“This is corporate welfare for a project that doesn’t have a lot of benefits for this community,” says Michael Weaver, an engineer.

He’s also a volunteer with a group called Great Lakes Neighbors United that is gathering signatures to recall Mr. Neitzke over the data center. To trigger a recall election, they must collect some 1,600 signatures by Feb. 15. Mr. Weaver is running separately for an open seat on Port Washington’s council, a nonpartisan body, in spring elections scheduled for April.

While Mr. Weaver’s politics lean left, he and others say local opposition to the data center crosses party lines. Many conservatives are concerned, for example, about the risks of AI as a tool for surveillance. “This gets people riled up on both sides,” says Christine Le Jeune, another volunteer.

Ms. Le Jeune pushes back against charges that data center opponents are hypocrites when they organize protests on social media. “This is a hyperscale AI data center. It’s not for my Facebook cloud,” she says. (Cloud services are currently the largest use of U.S. data centers, but AI is becoming a larger share as more such facilities come online.)

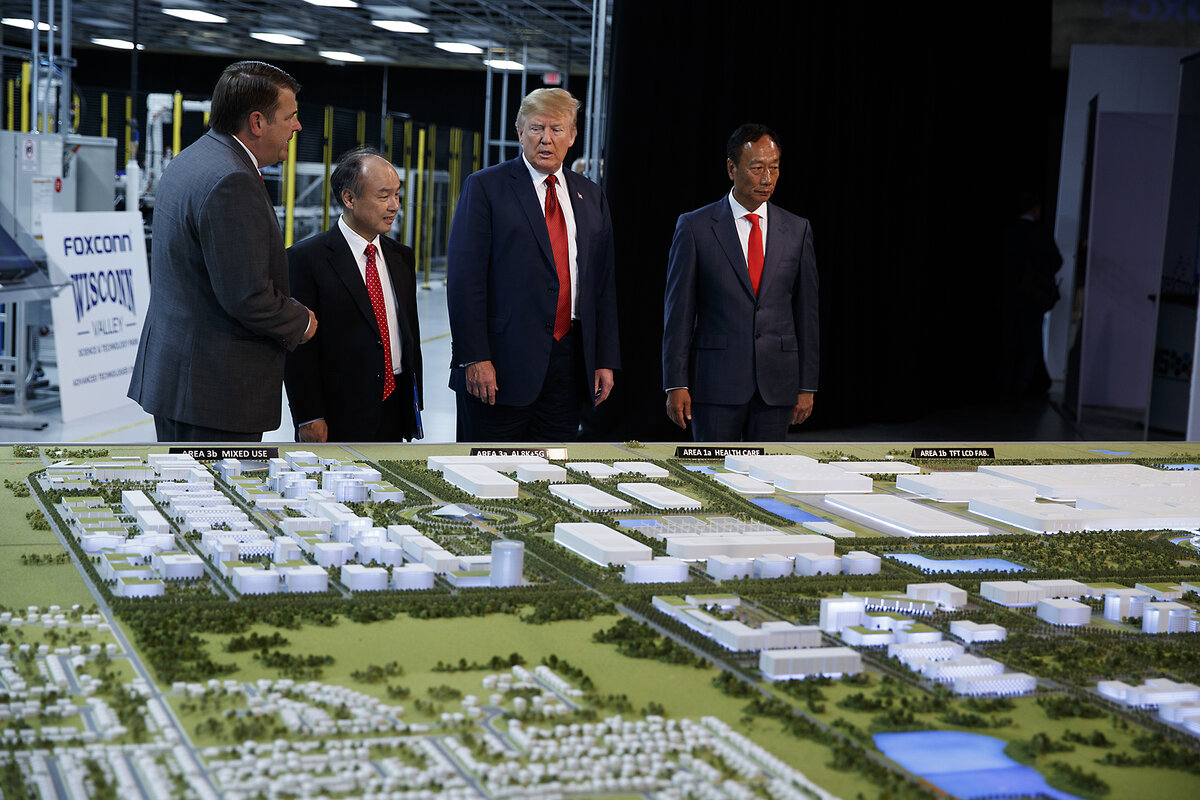

Meta, the parent company of Facebook, is building a $1 billion data center in Beaver Dam, 50 miles west of Port Washington. South of Milwaukee, Microsoft is due to open this year the first phase of a giant data center in Mount Pleasant. The Mount Pleasant site had previously been set aside for Foxconn, the Taiwanese company that assembles iPhones, to build a manufacturing plant for 13,000 workers – a facility that, in 2018, President Donald Trump promised would be “the eighth wonder of the world.”

Foxconn later abandoned that project, and skeptics say AI data centers could go the same way if AI company valuations collapse. Mr. Weaver says it’s unclear how Vantage could be held to account if it fails to fulfill its commitments to Port Washington.

President Donald Trump tours a facility intended for use by Taiwanese cellphone manufacturer Foxconn, in Mount Pleasant, Wisconsin, June 28, 2018.

New and upgraded transmission lines required

For now, construction crews are working around the clock to prepare the site. To supply the 1.3 gigawatts of power that the data center will need in its first phase, around 100 miles of new and upgraded transmission lines must be built. Clean Wisconsin, an advocacy group, calculates that the Port Washington and Mount Pleasant data centers combined will require power equal to 4.3 million homes, in a state that currently has 2.8 million housing units.

Port Washington says Vantage is obligated to pay for these upgrades, and consumers should not face higher rates as a result. Indeed, Mr. Teitz says consumers might actually benefit, as demand for power is growing in general and not just from data centers. “We’re at a moment of time where, quite frankly, we haven’t built enough generation or transmission to meet the overall electrification needs,” he says.

Some Wisconsin communities have successfully blocked data center projects. After opposition to a proposed Microsoft data center grew in the village of Caledonia, the company said it would find a new site.

The campaign in Port Washington kicked into a higher gear in September after Charlie Berens, a Wisconsin comedian and influencer, railed against its data center, claiming that Wisconsin “was becoming a dumping ground” for Silicon Valley. That attracted statewide attention and drew outside activists to council meetings, including a rowdy session in December where Ms. Le Jeune was arrested after refusing to leave the chamber.

“We were besieged by people who do not live here,” complains Mr. Neitzke. (Ms. Le Jeune, who faces a misdemeanor charge, says the environmental impact goes beyond Port Washington, so nearby communities are right to be concerned.)

While Mr. Neitzke knows some residents aren’t happy about the data center, he says the debate has been distorted by misinformation on social media, which the city has to respond to, even when it’s already set the record straight. Rumors used to spread around town in days, not hours. “Social media just changes the game. All you do is chase false narratives,” he says.

In a restaurant near City Hall, Vicki Benson is meeting a friend for lunch. She retired three years ago as a shipping manager at a manufacturing plant. She has followed local news about the data center – her husband is a reporter at the weekly newspaper – and has mixed feelings. She worries that newcomers will dilute Port Washington’s small-town feel and doesn’t believe Vantage’s promises on electricity prices. “Our utility bills will go up,” she predicts.

But she recognizes that data centers bring economic benefits. And she rejects opponents’ claims that Port Washington deliberately kept residents in the dark about the project. “The information was there. People just weren’t paying attention,” she says.

Mr. Weaver, of Great Lakes Neighbors United, admits that he used to follow state and national politics more closely than what’s happening on his own doorstep. Now, he’s running for a council seat and trying to engage more locally. If elected, “I’m going to try to be constructive and find creative solutions,” he says. “Not just say no to everything.”